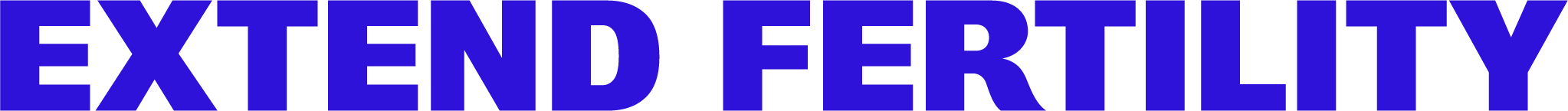

Egg count is one factor in age-related fertility decline. The other—and most important—factor is egg quality. Egg quality refers to the state of an egg as genetically normal or abnormal.

As you age, a higher and higher percentage of the eggs inside your ovaries contain genetic abnormalities.

The eggs inside your ovaries are “primordial,” or immature eggs. As you ovulate, they go through another phase of cell division, known as meiosis. Older eggs are more likely to accumulate errors in their DNA during that division process, leading to genetically abnormal eggs.

Once a cell’s DNA is degraded, it can’t be fixed medically or “healed.” In other words, once an egg becomes abnormal, it can’t become normal again—egg quality cannot be improved. Egg quality is fairly black-and-white—either an egg is genetically “normal” (euploid) or it’s not (aneuploid), and as women age, a higher and higher percentage of their eggs become abnormal.

Since DNA is like an instruction manual for our cells, any damage to your DNA can prevent that cell from doing what it’s supposed to do—which, in the case of the egg, is make a healthy baby.

Egg quality declines over time

There’s no test for egg quality. The only way to know if an egg is chromosomally normal is to attempt to fertilize it, and, if fertilization is successful, to perform a genetic test on the embryo. But because DNA damage is inevitable in older eggs, your age can give doctors a fairly accurate picture of what percentage of your eggs will be genetically normal.

When we talk about a woman’s egg quality, we’re talking about the expected percentage of her total number of eggs that are normal. For better or worse, this is purely a function of age. In stark contrast to the “wide range of normal” we see when it comes to egg count, the impact of age on egg quality is consistent and universal. In other words: women in their 20s will have mostly normal eggs, though they already have some abnormal ones. And women in their 40s will have mostly abnormal eggs—no matter how healthy a lifestyle they maintain.

Fertility and egg quality are directly connected.

Women’s ovaries are naturally programmed to allow just one egg to grow, mature, and be released (“ovulated”) each cycles (usually each month). That one egg represents the one chance for pregnancy in that particular menstrual cycle.

That egg ovulated may be either normal or abnormal. If it’s normal, great—you have a healthy pregnancy. But if it’s not? Abnormal egg cells typically don’t fertilize or implant in the uterus, but in the rare case they do, they can result in miscarriage or genetic disorders like Down syndrome.

The difference in egg quality between a 25-year-old and a 40-year-old is a matter of the statistical likelihood of the one egg she’s ovulated being normal. Because women in their late 30s and 40s have a higher percentage of abnormal eggs, it’s much more likely that their one egg each month will be abnormal. That’s why natural fertility declines with age, and why we see infertility, miscarriage, and genetic disorders more often with women over 35.

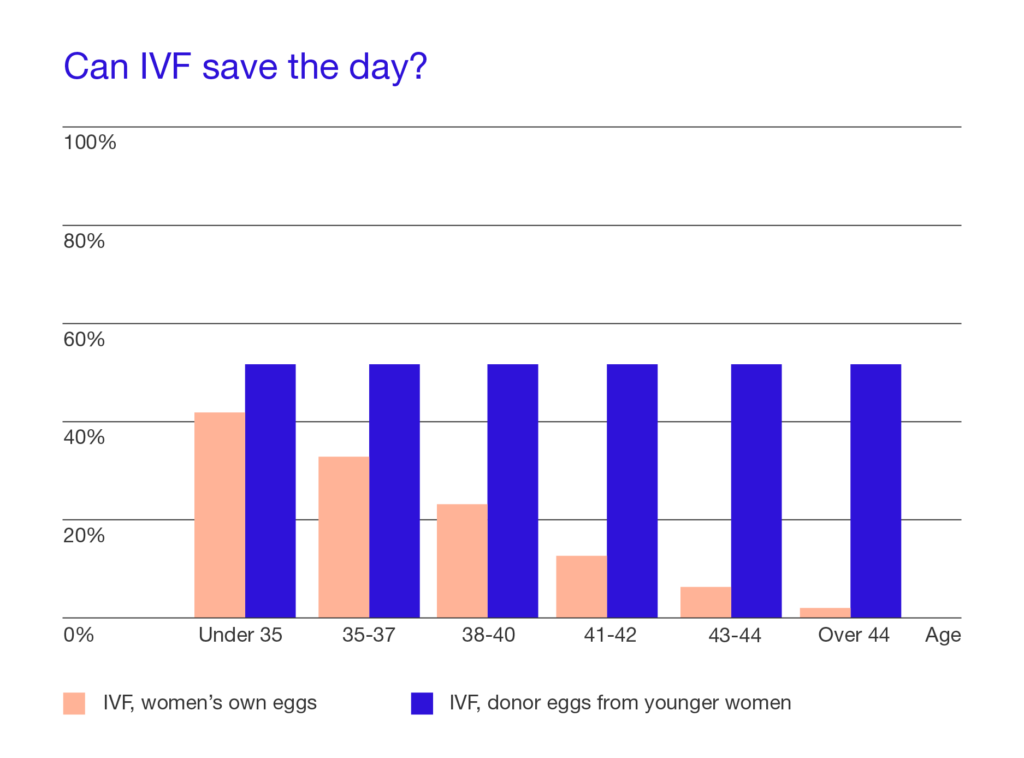

The age of the egg is the driving force in our chance at pregnancy.

Studies have determined that women doing in vitro fertilization with their own eggs of the same age experience a significant decrease in success rates (see chart below). However, for participants using donor eggs from a younger woman, the pregnancy rate was steady across all age groups: 51%.

This confirmed an important fact: because age directly correlates with egg quality, and therefore the ability of the egg to fertilize into a healthy pregnancy, it’s the age of the egg that matters most when it comes to fertility. Yes, there are some risks associated with carrying a pregnancy at what’s called “advanced maternal age” (namely a slightly higher risk of gestational diabetes and preeclampsia), but for the most part, it’s a young, healthy egg that makes for a healthy pregnancy.

That’s why egg freezing works—it allows women to freeze their young, healthy eggs and preserve their egg quality, so they can be their own egg donor later on.