Endo what? How endometriosis affects fertility—and how egg freezing can help

1 in 10 women experience this painful condition.

Since March is Endometriosis Awareness Month, it’s the perfect time to learn a bit more about this common condition, and how fertility preservation can help the women who suffer from it.

Official Trailer – ENDO WHAT? from ENDO WHAT? on Vimeo.

What is endometriosis?

Good question—but to answer it, we’ll have to start with a little anatomy lesson.

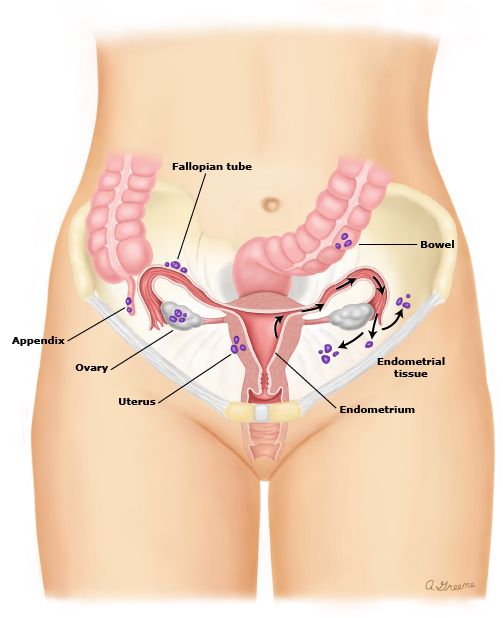

The lining of the uterus is known as the “endometrium.” This lining isn’t static; it actually changes and grows throughout a woman’s monthly cycle, responding to changes in estrogen and progesterone levels from the ovaries. In preparation for ovulation, it thickens, providing a cozy, nourishing place for a blastocyst (or fertilized egg) to implant and develop. If there’s no implantation (AKA no pregnancy), the lining disintegrates. The blood that’s present during menstruation? That’s no everyday blood—it actually contains the endometrium, which the body sheds in preparation for a new ovulatory cycle. This growth and regeneration is a normal part of the uterus’ function.

Contact Us to Chat with a Fertility Advisor

What’s not normal is when that endometrial tissue—which usually lives inside the uterus—begins to grow on other organs inside a woman’s body, like the ovaries, the outside of the uterus, or Fallopian tubes. These tissues grow, thicken, breakdown, and bleed just like the endometrium inside the uterus, except because they’re outside, this cycle can cause irritation or inflammation in surrounding organs or even produce scar tissue, known as “adhesions,” that can cause organs to attach to each other.

That’s called endometriosis, and it can interfere significantly with a woman’s entire reproductive system.

How does endometriosis affect the women who experience it?

Many women who have endometriosis experience pain as their number one symptom, especially painful cramps or heavy periods, thanks to the bleeding and inflammation of the endometrial tissue outside the uterus. This isn’t your average menstrual cramp. Women with endometriosis report cramping or pelvic pain that’s so severe, it can cause nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. This pain usually happens just before or during the menstrual period, but can sometimes linger all month. It’s chronic—meaning it happens consistently—and sometimes gets worse over time as the scar tissue grows.

Painful intercourse is also common, as scar tissue or endometriosis may be present between the vagina and an ovary, on the cervix, or on or behind the uterosacral ligament, which connects the cervix to the sacrum. Plus, if the endometriosis is present on the bowels or bladder, pain may also be felt during elimination or urination.

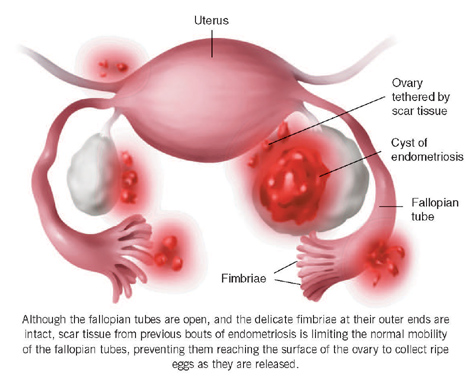

The other primary symptom of endometriosis is, unfortunately, infertility. Dr. Iris Orbuch, OB/GYN and endometriosis/laparoscopic surgery specialist, estimates that “40% of unexplained infertility is due to endometriosis,” and studies demonstrate that women with even mild cases of endometriosis have only a 2–4% chance of getting pregnant each month (compared to the 15–20% chance healthy women have). It’s believed that the “nodules” of endometriosis growth or the “adhesions” of scar tissue caused by the breakdown of endometrial tissue outside the uterus can damage the ovaries or Fallopian tubes, enter the ovary and cause ovarian cysts, block the movement of eggs from the ovaries to the Fallopian tubes, or prevent sperm from entering through the cervix. As Dr. Orbuch explains, endometriosis both “decreases a woman’s ovarian reserve [and] decreases fertility by either an anatomical distortion or via inflammation.” Any and all of these disruptions to the body’s normal function can affect fertility.

So who gets endometriosis, and why?

Studies suggest that up to 10% of women experience at least mild endometriosis. Diagnosis isn’t always straightforward, because so many of the symptoms—like pelvic pain during a period—are thought of normal parts of the way a woman’s body functions, or are commonly associated with other conditions. As stated in Endo What?, some women have to see 7–10 physicians in order to get a diagnosis of endometriosis, which is part of the reason that Dr. Orbuch and other experts are dedicated to raising awareness.

If a doctor suspects endometriosis, either because of a patient’s symptoms or because they felt an endometriosis “nodule” during a pelvic exam, they use laparoscopy, a surgical procedure, to confirm the diagnosis. During laparoscopy, the doctor makes one or more small incisions near the bellybutton so that they can insert a tiny camera, called a laparoscope, to observe the reproductive system and check for the nodules and adhesions that are characteristic of endometriosis. Usually, the doctor also takes a small sample of the tissue for a biopsy.

Even when the diagnosis is clear, though, doctors aren’t certain about what causes this condition. Research into risk factors, causes, and potential preventative measures is ongoing.

But is there a cure?

There’s no cure for endometriosis, but there are a few treatments that can reduce the symptoms, and the best treatment for each woman depends on her body and her life. If a woman’s primary concern with regards to the condition is pain, her doctor might recommend over-the-counter or prescription pain relievers. Another common treatment is hormone therapy, often in the form of birth control pills. Because endometriosis grows in response to estrogen produced during a woman’s ovulatory cycle, hormone therapy that reduces or controls estrogen production is thought to be an effective way to combat the pain of endometriosis.

In severe cases of endometriosis—in which hormone therapy or pain medication hasn’t helped—a doctor may recommend surgery. Laparoscopy, the technique used to diagnosis the condition, can also be used to allow a doctor to remove adhesions, nodules, or cysts. This kind of treatment often reduces or eliminates the pain for years, which is why Dr. Orbuch calls it the “gold standard” of endometriosis treatment. But the benefits provided by surgery are ultimately temporary; the nature of endometriosis is that the rogue tissue will eventually begin to grow anew.

In certain cases, if all other treatments fail and the severe pain and complications of endometriosis impact a woman’s quality of life so significantly, a doctor may recommend the removal of one or both ovaries and/or the uterus. This irreversible solution may be an option for women who have already had all the children they desire to have (or for women who don’t want children), and can provide a permanent solution to the debilitating symptoms of endometriosis.

Treating the infertility caused by endometriosis is another issue entirely. Because endometriosis is a chronic disorder that produces a physical blockage to the reproductive system—with no known cure—the success rates for women trying to conceive with advanced endometriosis are low (think monthly odds of pregnancy under 2%). In vitro fertilization is the most effective way to bypass damage and physical blockages within the reproductive system, and therefore it offers the best chance for pregnancy in women with severe endometriosis.

Okay, I understand the disorder now—but what does this have to do with egg freezing?

Let’s review: endometriosis involves endometrial tissue, normally found inside the uterus, growing on other organs in the pelvic area, causing inflammation, scarring, cysts, and organ damage. Included in that last category is damage to the ovary, which is responsible for producing, maturing, and releasing eggs. If the ovary is damaged? Impaired egg production or ovulation—or none at all. And fertility treatments like ovarian stimulation can’t always help, once the condition has progressed. Additionally, while surgical treatment of endometriosis offers long-term pain relief, studies show that it may actually reduce ovarian reserve (and therefore fertility) by inadvertently removing healthy ovarian tissue or cutting off blood supply to the ovary.

That’s where egg freezing comes in. Because endometriosis puts women at risk for ovarian damage, women with endometriosis who aren’t yet ready to get pregnant are excellent candidates for fertility preservation techniques, like egg freezing. “I always encourage my patients to consider egg freezing long before they are ready to consider child bearing,” explains Dr. Orbuch.

If possible, it’s best for women with endometriosis to freeze their eggs while they’re young and the condition is still in the early stages, as that’s a. when their ovaries will respond best to stimulation, and b. when potentially complicating factors like cysts are less likely to be present. Then, when they’re ready to start a family later, they can use those eggs—along with in vitro fertilization—to give them the best chance of conceiving, even in the face of advanced endometriosis.

Long story short:

Not only does endometriosis cause chronic pain for 1 in 10 women, it’s also a leading cause of infertility. Freezing eggs before the ovaries are damaged by this condition offers a “real chance of future pregnancy.”

Still want to learn more about endometriosis? Check out Shannon Cohn’s documentary Endo What?, explore endometriosis.org and the resources below, or ask our doctor on Twitter or Facebook.

More resources:

Endometriosis: A Guide for Patients from the American Society for Reproductive Medicine

Frequently Asked Questions: Endometriosis from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

Endometriosis: Beyond the Basics from UpToDate